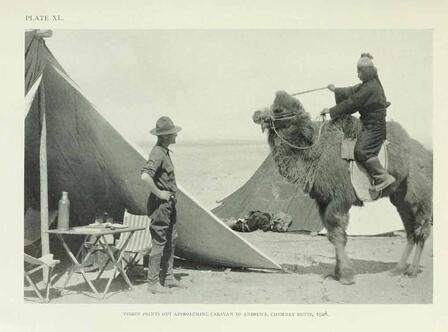

Roy Chapman Andrews in the field

I raced through my wife’s gift, Quest in the Desert by my boyhood hero, Roy Chapman Andrews–the story of an expedition to Mongolia in the 1920s, and the wild adventures of the leader and his dog. These are avatars of Andrews and his dog, to whom he dedicated the book; and the adventures are based on his actual experiences.

I was expecting a rip-snorting yarn, and I got one. What I wasn’t expecting was an undertone of sadness that will haunt me for a while.

The Mongolia that Andrews fell in love with is long gone, the world he inhabited is only a memory–and I’m old enough now to empathize with that. My world’s pretty much gone, too, and I don’t much like the one that’s replaced it. And yet there’s more to it than that.

I somehow got the impression of a man who, wherever he went, didn’t quite fit in. Certainly he was needing something that he couldn’t seem to find.

And then, watching some film footage of Andrews’ expeditions, it occurred to me that maybe the wistfulness was in me, not the writer. Watching the black-and-white ghosts of Andrews’ bygone world, I found myself longing for it in some way that I could hardly understand.

I have read much of Andrews’ non-fiction, and now I’ve read his novel, written more than twenty years after he had to leave Mongolia for good, the communist regime having kicked out all the Westerners. And now I think I know what Roy Chapman Andrews was missing–mind you, my conclusion is based only on the words he committed to publication.

There is no sign, in any of this printed work, that the author had any communion with the God who created him, whose Son redeemed him. And looking out on our God-rejecting age–which, with a little bad luck and a lot of stupidity and wickedness, could turn out looking like Northern China in 1926–it makes me think that a human being without God is incomplete, and will never be complete. There is only so far we can go without Him, and that’s not far enough.

Which, I believe, was the broken part of Roy Chapman Andrews. He traveled very far indeed, but never far enough.

Like this:

Like Loading...